Suicide Among College Students

Ewa K. Zielinska, University of New Haven

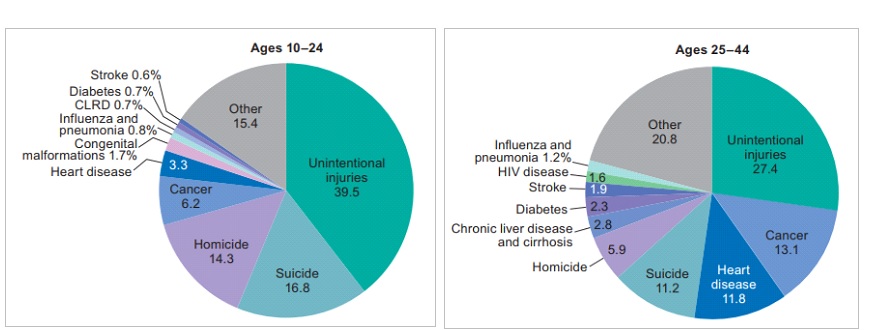

Suicide, “an inward-directed act of violence,” has been a consistent problem in the United States and internationally (Title & Paternoster, 2000). According to the 2016 National Center for Health Statistics Brief, “suicide is an important public health issue involving psychological, biological, and societal factors” (Curtin, Wagner, & Hedegaard, 2016, p. 1). Based on data between 1999 and 2013, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) places suicide as one of 15 leading causes of death for individuals between 10 and 64 years of age, especially among adolescents and young adults. In 2013, suicide was the second leading cause of death among all races and sexes for ages 10-24, and the fifth for ages 25-44 (see Figure 1.)

Figure 1. Percent distribution of 10 leading causes of death, by age group: United States, 2013. Adopted from “Deaths: Leading Causes for 2013.” (2016). National Viral Statistics Reports, 65(2), 1-95. Retrieved November 12, 2017 from www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr65/nvsr65_02.pdf.

From a theoretical standpoint, consistency in suicide statistics throughout the years has led to further research on the issue. According to Emile Durkheim, the author of the groundbreaking 1887 sociological case study on suicide, the behavior is a result of both psychological and social factors (Crossman, 2017). Based on those factors, Durkheim classified suicide into three types: egoistic (associated with depression), altruistic (linked to personal duty), and anomic (related to social deregulation) suicide (Jones, 1986). What is more, Durkheim’s study of suicide is partially consistent with current government statistics. According to Durkheim’s findings, suicidal tendencies progress steadily beyond 15 years of age into older age. As a result, suicide can occur in any point in our life from adolescence on (Durkheim, 1951).

Explaining the underlying cause of suicide is a complex issue. This paper concentrates on recent studies and their attempt to explain the underlying causes of suicide among college students, and identify groups that are most prone to suicide. In addition, policy implications and directions for college suicide prevention programs are discussed. Finally, the paper concludes by providing recommendations for future research.

Suicide Among College Students

A recent study conducted by Mortier and colleagues (2017) looks at indicators that increase the likelihood of the first onset of suicide in college. Previous research identified a multitude of risk factors including family functionality (e.g., critical/harsh parenting), adolescent mental health (substance abuse, depression, and conduct problems), problems with peer relations, and academic struggles (Hawton, Saunders, & O’Connor, 2012). However, no previous study looked specifically at the risk for suicidal thoughts and behaviors (STB) while in college.

Trauma and the Importance of Parents

The researchers used a sample of 2,337 incoming freshman to conduct a longitudinal study (Mortier et al., 2017). Using the interview method, data were collected on STB, parental psychopathology, childhood-adolescent traumatic experiences, 12-month risk for mental disorders, and 12-month stressful experiences. The findings indicated that the strongest predictors of the first onset included dating violence prior to the age of 17, physical abuse prior to the age of 17, and 12- month betrayal by someone else other than the partner. Given that incoming college students are at a higher risk of suicidal onset than the general population, the researchers proposed implementing a cost-effective clinical screening and trauma assessment upon entering college. Such assessment would help identify students with the highest number of suicidal risk predictors (Mortier et al., 2017). Moreover, as suicidal behavior is related to trauma, the researchers suggested on-campus bystander programs targeting dating violence. This study was the first attempt to investigate risk factors for suicidal onset in college. As a result, future research should use a larger sample of students, preferably freshmen through seniors, to shed more light on additional risk factors and timing of suicidal onset (Mortier et al., 2017).

Intimate Partner Violence & Sexual Assault Victimization

The findings presented by Mortier and colleagues (2017) confirm the conclusions made by Wolford-Clevenger (2016) regarding the relationship between intimate partner violence and the likelihood of suicidal thoughts. In this study, researchers examined specific categories of intimate partner abuse (physical, emotional, harassment) in relation to gender. Based on previous research on college students, indicating that women experience less physical abuse than men, the study hypothesized that women are likely to report less physical abuse (but not harassment or emotional abuse) than men (Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2016). Moreover, the researchers predicted that suicidal ideation and depression symptoms are likely to increase with more frequent harassment, physical abuse, and emotional abuse. Finally, emotional abuse is believed to be the strongest predictor for suicide among women.

Based on a sample of 502 college students, mainly composed of Whites (65.7%), freshmen (64.9%), and women (63.5%), the researchers examined the impact of gender differences and physical and emotional intimate partner violence on suicidal thoughts. The participants filled out a series of questionnaires on demographics, intimate partner violence, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation (Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2016). Using longitudinal analysis, the results indicated that about 10% of the sample showed some level of suicidal thought. Moreover, over half of the students (54%) experienced some level of intimate partner violence, harassment (30%), emotional abuse (45%), or physical abuse (26%). Based on a regression model, men who experienced physical rather than emotional abuse were more likely to display suicidal thoughts. On the contrary, emotional abuse was a significant predictor of suicidal thought in women (Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2016).

Future research should expand on this study by collecting data on participants’ relationship status, as violence can vary when the participant is in a relationship or single; partner’s gender, as violence often depends on the gender of the perpetrator; substance abuse, unemployment, social support, and feelings of hopelessness (Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2016). In terms of policy and practice, given that different types of abuse were related to suicidal thought for men and women, the researchers suggest on and off campus screening for history or current signs of both physical and emotional abuse, or harassment from intimate partners (Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2016).

The relationship between sexual assault and suicidal thought in college was further explored by Keefe and colleagues (2017). Consistent with previous research findings (PinhasHamiel et al., 2009; Tomasula et al., 2012; Anderson et al., 2015), the study argued that there is an increased risk of suicide among all adolescents reporting sexual assault (Keefe et al., 2017). The researchers used a randomly selected sample of 1,677 undergraduate students, predominately Caucasian freshman women, and utilized a number of questionnaires to collect data on participants’ demographics, sexual assault history, suicidal thoughts, depression, anger/hostility, and disassociation. Based on the cross-sectional analysis, the findings indicated a positive relationship between sexual assault and suicidal thoughts. What is more, students who showed increased hostility and disassociation related to sexual assault were at a significantly higher risk of suicidal thoughts (Keefe et al., 2017).

Program & Treatment Recommendations

Current results support the call for educating the public, giving clinical attention to sexual assault survivors, and developing “targeted prevention and intervention programming that will produce potentially life-saving results for adolescents at risk” (Anderson, Hayden, & Tomasula, 2015, p. 538). In terms of policy and practice recommendations, similar to previous research, the findings support combating suicidal ideation though screening and treating sexual assault survivors for emotional polarity (Keefe et al., 2017). More specifically, the researchers recommend that programs not only look at depression and anxiety, but also trauma-related reactions to sexual victimization, especially anger and disassociation (Keefe et al., 2017). What is more, future research should expand the analysis by looking at different types of gender-specific sexual assault and the role of alcohol use on impulsivity and anger. This in turn will help identify specific interventions for those at the highest risk of suicidal ideation (Keefe et al., 2017). Interestingly, the study by Wolford-Clevenger and colleagues (2016) already identified some of the limitations presented by Keefe and colleagues (2017). In order to prevent suicide among college students, both on and off campus health care facilities should provide abuse and suicide screening (Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2016).

Sexual Assault & Gender

Given that there is a significant gender effect in the relationship between sexual assault and suicidal ideation, an interesting question for future research would be: What is the relationship of sorority membership, sexual victimization, and suicidal thoughts? Two recent studies identify college women, especially sorority members, as one of the most vulnerable groups to sexual assault victimization (DeKeseredy et al., 2017; Franklin, 2016). Both studies use college samples to look at the relationship between sorority membership, risk taking, and the likelihood of becoming a victim of a sexual assault. The findings indicate that sorority members are more likely to consume larger volumes of alcohol, engage in risky behavior, and chose abusive partners and friends. As a result, an example of an effective program implemented on college campuses, and aimed at combating sexual violence, is the Green Dot Violence Prevention Program (DeKeseredy et al., 2017). Students are trained to become “active bystanders” who recognize and respond to on-campus high risk situations that are likely to result in sexual victimization. Additionally, program participants are encouraged to promote sexual violence awareness through a multitude of proactive on and off-campus activities called green dots, such as attending an awareness event with three male friends, or discussing the importance of power-based violence with women in your family of friend circle.

Studies on the effectiveness of this program show that trained students were less likely to accept witnessing sexual violence and more likely to intervene than non-trained students (DeKeseredy et al., 2017). Similar to recommendations provided by DeKeseredy and colleagues (2017), Franklin (2016) emphasized prevention-oriented educational programs, specifically, teaching students to recognize signs of potential danger, assess threats, and how to respond to them. Furthermore, Franklin (2016) recognized that combating sexual violence entails understanding why and where such violence occurs. Finally, being able to estimate personal risk and predatory intentions of potential offenders is especially critical among sorority women interacting with fraternity men (Franklin, 2016). Additionally, Rinehart and colleagues (2017), whose findings indicate that positive attitude towards casual sex decreases women’s perception of risk of victimization, suggested that increasing risk perception is key in combating sexual violence on campus. More specifically, improving women’s assessment of their own risk, by identifying underlying cognitive processes, should be the focus of prevention efforts. The researchers suggested concept and active learning techniques designed to promote learning about sexual assault, to better assess risk when presented with a scenario (Rinehart et al., 2017).

Conclusion

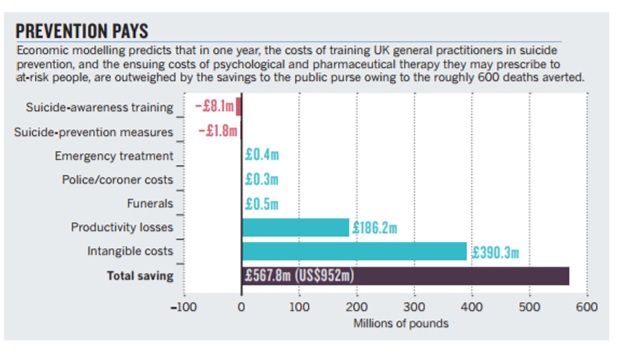

The majority of discussed studies emphasize the importance of further research on mental health and the implementation of suicide detection-oriented screening processes for college students. From an international standpoint, the cost of providing suicide prevention methods and awareness training are outweighed by the savings to the public (see Appendix A). It would be interesting to look at the same model and cost comparison from the United States’ perspective and determine possible savings (Aleman, & Denys, 2014).

References

Aleman, A., & Denys, D. (2014). A road map for suicide research and prevention. Nature, 509, 421-423. Retrieved September 7, 2017, from https://www.nature.com/polopoly_fs/1.15245!/menu/main/topColumns/topLeftColumn/pdf/509421a.pdf?origin=ppub.

Anderson, Laura M., Hayden, Brittany M., Tomasula, Jessica L. (2015). Sexual Assault, Overweight, and Suicide Attempts in U.S. Adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behavior, 45(5), 529–540. doi:10.1111/sltb.12148

Crossman, A. (2017). Learn About Emile Durkheim's Classic Study of Suicide in Sociology. Retrieved September 08, 2017, from http://www.thoughtco.com/study-of-suicide-by-emile-durkheim-3026758

Curtin, Wagner, (2016). Data Brief. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved September 08, 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db241.pdf.

“Deaths: Leading Causes for 2013.” (2016). National Viral Statistics Reports, 65(2), 1-95. Retrieved September 7, 2017 from www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr65/nvsr65_02.pdf.

DeKeseredy, Walter S., Hall-Sanchez, Amanda, Nolan, James. (2017). College Campus Sexual Assault: The Contribution of Peers’ Proabuse Informational Support and Attachments to Abusive Peers. Violence Against Women, 00(0), 1-14. doi: 10.1177/1077801217724920.

Durkheim, Emile. (1951). Suicide: A study of sociology. London and New York: Routledge Classics.

Franklin, Cortney A. (2016). Sorority Affiliation and Sexual Assault Victimization: Assessing Vulnerability Using Path Analysis. Violence Against Women, 22(8), 895-922. doi:10.1177/1077801215614971.

Jones, Robert Alun. (1986). Emile Durkheim: An Introduction to Four Major Works. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, Inc., 82-114.

Keefe, Kristy M., Hetzel-Riggin, Melanie D., Sunami, Naoyuki. (2017). The Mediating Roles of Hostility and Dissociation in the Relationship Between Sexual Assault and Suicidal Thinking in College Students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 00(0), 1-19. doi: 10.1177/0886260517698282

Mortier, P., Demyttenaere, K., Auerbach, R., Cuijpers, P., Green, J., Kiekens, G., Kessler, R., Nock, M., Zaslavsky, A., Bruffaerts, R. (2017). First onset of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in college. Journal of Affective Disorders, 207, 291-299. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.033.

Rinehart, Jenny K., Yeaters, Elizabeth A., Treat, Teresa A., Viken, Richard J. (2017). Cognitive processes underlying the self–other perspective in women’s judgments of sexual victimization risk. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, XX(X), 1-19. doi:10.1177/0265407517713365.

Tittle, C. R., & Paternoster, R. (2000). Social deviance and crime: An organizational and theoretical approach. Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury Publishing Company.

Wolford-Clevenger, Caitlin, Vann, Noelle C., Smith, Philip N. (2016). The Association of Partner Abuse Types and Suicidal Ideation Among Men and Women College Students. Violence and Victims, 31(3), 471-485. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-14-00083.

Adopted from Aleman, A., & Denys, D. (2014). A road map for suicide research and prevention. Nature, 509, 421-423. Retrieved September 7, 2017, from https://www.nature.com/polopoly_fs/1.15245!/menu/main/topColumns/topLeftColumn/pdf/509421a.pdf?origin=ppub.

Recent Articles

"EBP Day" Event Login Portal

Evidence-Based Professionals' Monthly - December 2025

Evidence-Based Professionals' Monthly - January 2026

Evidence-Based Professionals' Monthly - February 2026

Substance Use Disorders (SUDs) Masterclass: Core & Advance Skills for Evidence-Based Practitioners

Trauma Informed Care Services

EBP Day - Our Free Annual Planning Event

Evidence-Based Professionals' Monthly - November 2025